Believe me Audio book short story

Description

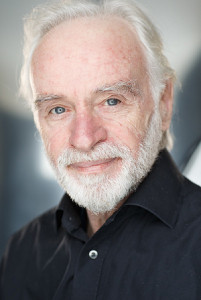

Vocal Characteristics

Language

EnglishVoice Age

Middle Aged (35-54)Accents

Irish (Eastern- Leinster, Dublin) Irish (General)Transcript

Note: Transcripts are generated using speech recognition software and may contain errors.

So what can I tell you about him? Well, he could single, right? Knew all the words to this, believe me if all those endearing young charms. But what about the man he Waas? What about where this man found his joy? I know he did love a funeral. That was his thing. He found no joy at the job, that's for sure. 30 years stood watching over rooms of paintings he didn't understand, made by artists whose names he could barely pronounce. An overweight sack of body odour trapped in a polyester uniform stood in the corner of the gallery, invisible to the well heeled crowd that glided past every day, making themselves feel more worthy with the doors up of culture. But he did love a good funeral. He would go to the funerals of people he didn't know to represent. The family he said he used to raid them had set ideas on what constituted a good funeral. Mostly, it was whole generous. They were with drink. Here were the twin pillars of how to rate a funeral drink served and how much singing was encouraged. People had to be respectful, solemn lowered their eyes as the coffin passed dress appropriate to the day. Black tie, neatly knotted top shark button done up, laundered and ironed handkerchief ingest pocket off jacket. And no focus Jane's. Then back to the house, the doors would be wedged open and Mourners ba gathered in huddles, in the kitchen and in the back room and in the partner or beside up on the landing stairs. All the people had a drink put in their hand, and they remembered the dead. And then they sang. The worst sin was when the family handed you a bottle of weak lager from the supermarket in some small sandwiches. And that was your lot. Oh, could you send someone off and be so miserable about it? He'd say. He said there had been funerals when he actually felt ashamed for the corpse. We have to make sure there's lots of drink, and it's always that the English didn't know how to die, he said. They didn't know how to organise a good delivery into the next world. They would give your cups of tea and cut off sandwiches and stand around being embarrassed, as if death itself was a lapse into bad manners. I think what he appreciated most was the formality of grief. Sorry for your troubles. Have a glass, Dennis. Okay, So sorry for your loss, reader. Have another Dennis just a small one and overgenerous till the paddy bottle Give us a song. No, I couldn't go on, Dennis. Maybe later. Make a space for Dennis there and then he would be persuaded to it. It was the formality, the way you could wrap up all emotions into a tight fist of modest condolence and correctly knotted ties on glasses refilled on DH, then real Eastham through song. There wasn't much opportunity for song in his life. That's why he loved the funerals. You heard of Count John McCormack? Everyone said he sang like John McCormack. They would be gathered after the funeral into the parlour, The old buys. And they would say, Give us a song, Dennis. And he would say, No, no, I can't. But he knew they would keep on insisting on DH. Someone would refill his glass so he would stand and they would hush the people in the corner that was still talking. They would go silent and the silence would spread to all the rooms in the house. Only then would he begin, and that was him then those moments. Those were the moments when he was best in the world. When he was alive, of course, there was drink. They all had a drink. It was no thing for a man to be drinking. Everyone was quieted and listening at him, standing in the middle of the floor, launching into Believe me. If all those endearing young charms there would be nothing but the sound of his lonely, unaccompanied song pervading through the house and all its corners, the rich tenor holding the notes, turning the words around in his mouth, his eyes closed and fierce concentration, the glass of Paddy's held like a chalice at the Eucharist, the congregation frozen, an absorption caught up in the reverence with which he sang. And then Jim Guillon would start to cry and talk about his mother dead 20 years earlier, and when Jim Guillon cried, he always had a nose played. Of course, Guillen never had a clean handkerchief in his life, and so Dennis would have to remove the one from his top pocket and give it to Jim to staunch the blood. But he knew all the words to believe me. If all those endearing young charms it was his moment. You see, it was his hour when he was connected. It was really It's important to remember that we cannot miss those moments. We have to recognise them. And that was his moment. I see that now. I didn't see it then. I didn't understand what he was trying to impart when he sang, but I see it now. I understand it now. Dillon died to a few weeks back. One of the last of the old boy's gun. His useless sons organised the cheapest 10 to the back room of their local. If you curled up sandwiches and bowls of crisps on DH, not a penny behind the bar. And they got a deejay, some clown with a CD player and a Paris speakers blaring out Irish songs. The fields of Athan Ray and Jim Guillon sons at the funeral of their father in their T shirts, and they're ******* jeans. At one point, Jim's last remaining powers had enough and got the deejay to switch off its speakers. Go on, Dennis, give us a song. So he rose to his feet slowly unsteady, spelling some of his glass. He composed himself while a bunch of young ones kept laughing in the corner. He started in on the song, Believe me, if all those halfway through the first verse, he lost the words he started again, but that only seemed to befuddle him more. Some more of the crowd went back to their conversation, ignoring him as he tried to shift to the course on then to sing louder to the men above the raising chatter. Finally, the deejay put on Fairytale of New York, and people turn their heads away and quietly. He sat down confused, defeated aides spent his life standing in a corner, protecting bits of art he didn't understand, and he hated it. He hated it right up until the day his manager opened. His work locker on the empty bottles fell out, and he sacked him on the spot. All he wanted was to sing, and that's no T crowd, the arty lot looking up at the dead paintings. They couldn't see that they had an actual artist, a really living artist right there, among them. That middle aged man stood over by the fire extinguisher with the broken blood vessels on his nose and the guts straining the buttons on his regulation. Short on with that stupid ******* hat. They made him where they couldn't see the man, let alone recognise the artist. But that is what an artist is. The artist is the one who needs needs you to understand, to express his art. The singing was breathing to him. And when he could no longer breathe, he died. It was only at the funerals. That was where he had been allowed to express his art and to live. That was where he found his joy. Don't try to rub him off that, don't you? Who **** on that?